Arroyo Verde Park in Ventura, California Wild Collected

Photo by Patrick Houston Briggs

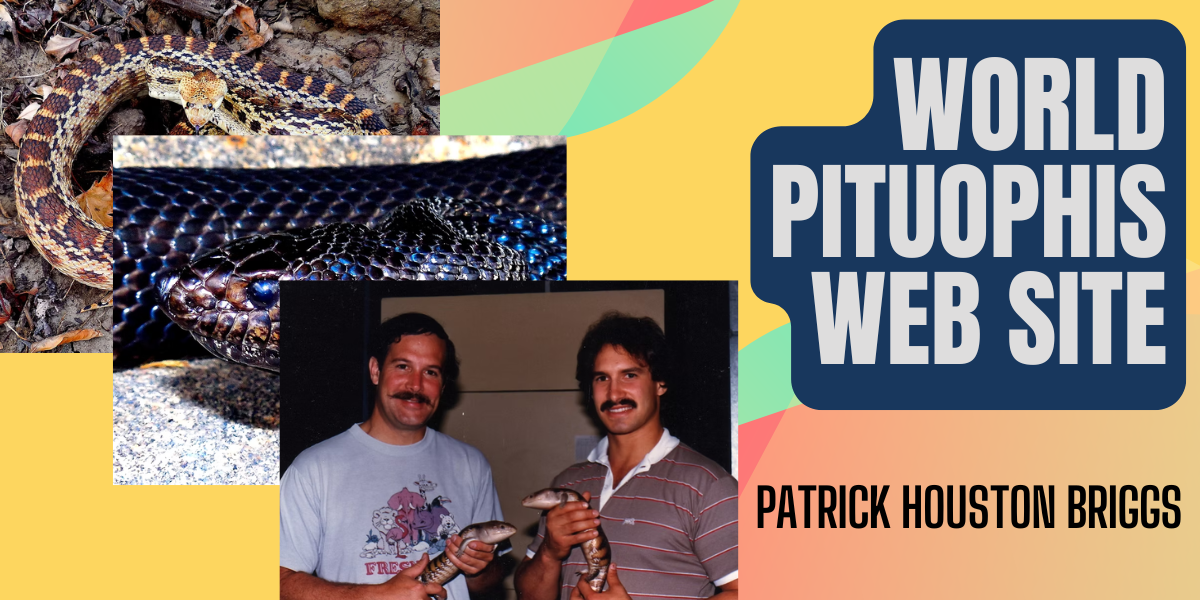

THE SAN DIEGO GOPHER SNAKE (Baird and Girard, 1853)

BY PATRICK HOUSTON BRIGGS

The San Diego Gopher snake Pituophis catenifer annectens is a race that because of its range, actually would be better called the Southwestern Coast Gopher snake. Indeed its range begins southerly 20 miles or more south of El Rosario in Baja California, Mexico of the west coast extending northerly along the coast well past San Diego, California reaching even San Luis Obispo and barely into Monterey Counties in California of the United States where it begins to intergrade in certain areas of this region with the Pacific Gopher Snake Pituophis catenifer catenifer. The further inland from the coast it occurs, the more southerly it seems to intergrade or be replaced altogether with the Pacific Gopher Snake. It has been found in San Luis Obispo 320 miles north of San Diego and even futher another 2 digit number of miles into Monterey County.

Pituophis catenifer annectens SAN DIEGO GOPHER SNAKE 1.0 closeup head study

Old adult Wild Collected San Diego, California

Photo by Patrick Houston Briggs, Courtesy Tom Derr

Pituophis catenifer annectens SAN DIEGO GOPHER SNAKE 1.0 old adult Wild Collected

San Diego, California

Photo by Patrick Houston Briggs, Courtesy Tom Derr

Pituophis catenifer annectens SAN DIEGO GOPHER SNAKE RACE neonate 0.1

San Louis Obispo County, California

Photo by Patrick Houston Briggs

Pituophis catenifer annectens SAN DIEGO GOPHER SNAKE RACE 0.1 adult

San Louis Obispo County, California

Photo by Patrick Houston Briggs

Pituophis catenifer annectens SAN DIEGO GOPHER SNAKE RACE

San Louis Obispo County, California

Photo by John Sullivan

Pituophis catenifer annectens SAN DIEGO GOPHER SNAKE RACE

San Louis Obispo County, California

Photo by Bill Bouton, March 10, 2013

Pituophis catenifer annectens SAN DIEGO GOPHER SNAKE RACE neonate wild collected

Ventura, California Under the HWY 101 on the Santa Clara River

Photo by Patrick Houston Briggs

The subspecific epithet annectens in Latin means “to connect”. This is appropriate for the race, because the anterior dorsal blotches of this ophidian interconnect, fuse, or blend with each other and the lateral secondary spots and markings. Also the anterior markings are darker and bolder than those toward the mid-region of the snake. The neck ground color is usually a smudgy orange with a dark black pattern of touching spot markings, and in some individuals, it seems to be composed of nothing more than numerous dark round connecting spots. Generally, San Diego gopher snakes may be simply brown and black with some drabby grayish suffusion on a cream, straw, or buff body ground color. Others sport very beautiful tones of yellow and blending reds, rusts, or orange and varying shades of brown, tan, or cream dappled with black. These gopher snakes normally carry a blotched pattern above and 4-5 series of lateral spotting along each side, but striped individuals also occur. They are striking, so herp enthusiasts breed them for collectors. The pet trade also selectively breeds albinos, leusistics, axanthics, hypo and hypermelanistcs, and many other desired aberrations of color or pattern in these ophidians. It has a tail proportionately longer than any other form of this genus (Stull 1940).

Reproduction and Food:

San Diego gopher snakes breed in Spring and lay eggs that hatch usually from late July through October at around 15 inches in length (38 cm.) and grow from about 2.5 – 7 feet long (76 – 213 cm. They are generally diurnal, but will become active at night when temperatures are high searching out small rodents, birds and their eggs, and occasionally, lizards.

Conservation Status: Pituophis catenifer annectens has not been included on any Special Animals List and the Endangered and Threatened Animals List which are published by the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, therefore it seems quite apparent that the state of California has no serious conservation concerns for this ophidian form.

Pituophis catenifer annectens SAN DIEGO GOPHER RACE neonate

Deep Creek San Bernardino Mountains in California

Digital Image by Patrick Houston Briggs, Courtesy to Jerry Hartley

Midbody Scales 29-35 (usually 33)

Ventrals 210-253

Caudals 60-84

Frontal usually undivided but occasionally split partially

Prefrontals Usually 4, but occasionally 2 or if azygous scales are present and included, more than 4

Rostral Low and is as broad as long penetrating usually 1/3rd to the full distance between the internasals

Supralabials 7-10 (usually 8 or 9) (the 4th, 5th, or none contacting the eye)

Infralabials 11-15 (generally 12 or 13)

Preoculars 1-3 (usually 2)

Loreal Present and many times, separated into 2 or 3 scales

Azygos Often found between frontal and prefrontals between prefrontal and preocular of either side, or between 2 pairs of prefrontals, or behind the rostral.

(Many of these counts are from O. Stull 1940) Pituophis catenifer annectens can be distinguished from Pituophis catenifer catenifer by having the larger number of both ventral and caudal scales ( the total greater than 300) and by having more dorsal blotches (rarely less than 90 and generally more than a 100.

Pterygoids 8-14 slightly smaller than the palatines and progressively decreasing in size

towards the rear.

Dentition:

Mandibular teeth 18-20 decreasing slightly in size toward the back.

Maxillary teeth 14-18 decreasing slightly in size posteriorly.

Palatines 9-10 somewhat smaller than both the mandibular maxillary teeth.

Pituophis catenifer annectens SAN DIEGO GOPHER SNAKE 0.1 upper head study

Adult Wild Collected San Louis Obispo, California

Photo by Patrick Houston Briggs, Courtesy Sean McKeown

Pituophis catenifer annectens SAN DIEGO GOPHER SNAKE 0.1 upper head study

Adult Wild Collected San Louis Obispo, California

Photo by Patrick Houston Briggs, Courtesy Sean McKeown

Pituophis catenifer annectens SAN DIEGO GOPHER SNAKE 0.1 upper head study

Adult Wild Collected San Louis Obispo, California

Photo by Patrick Houston Briggs, Courtesy Sean McKeown

Pituophis catenifer annectens SAN DIEGO GOPHER SNAKE 0.1 upper head study

Adult Wild Collected San Louis Obispo, California

Photo by Patrick Houston Briggs

Pituophis catenifer annectens SAN DIEGO GOPHER SNAKE 0.1 upper head study

Adult Wild Collected San Louis Obispo, California

Photo by Patrick Houston Brigg

Pituophis catenifer annectens SAN DIEGO GOPHER SNAKE 0.1 upper head study

Adult Obese Wild Collected San Diego, California

Photo by Patrick Houston Briggs

Dick Dunn carries Pituophis catenifer annectens Photographer Unknown Internet Image

Pituophis catenifer annectens SAN DIEGO GOPHER SNAKE RACE

Annectens from its most northerly range: Elk Horn Slough, Monterey County California RibbitPhotography.jpg from the internet Unknown photographer name

Pituophis catenifer annectens SAN DIEGO GOPHER SNAKE Lloyd and Sunnie Lemke line

Photo by Patrick Briggs

Pituophis catenifer annectens SAN DIEGO GOPHER SNAKE wild collected male

Moro Bay coastal California locality

By Patrick H. Briggs, Courtesy Sean McKeown, herpetologist for the Fresno Chaffee Zoo

Pituophis catenifer annectens SAN DIEGO GOPHER SNAKE Lloyd and Sunnie Lemke line

Photo by Patrick Briggs

Arroyo Verde Park in Ventura, California Wild Collected

Photo by Patrick Houston Briggs

Pituophis catenifer annectens SAN DIEGO GOPHER SNAKE 1.0 closeup head study

Photo by Patrick Houston Briggs, Courtesy Rick Lewis

Pituophis catenifer annectens SAN DIEGO GOPHER SNAKE 1.0 closeup head study

Photo by Patrick Houston Briggs, Courtesy Rick Lewis

Pituophis catenifer annectens SAN DIEGO GOPHER SNAKE TWO-HEADED wild collected

Santa Barbara California locality

Photo by Patrick Houston Briggs, Courtesy Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History

Bob Applegate on the left, a top breeder of snakes and lizards with Patrick H. Briggs

Photo taken by Paul Slocumb